Why Performance Reviews Fail Women—And How Systems Thinking Fixes It

Performance reviews aren’t just about individuals—they’re shaped by systems. In this must-read article, Dr. Aria Jones explores how unconscious gender bias seeps into performance evaluations, often reinforcing inequity across organizations. Using a systems dynamics lens, she reveals how feedback loops, structures, and blind spots can perpetuate disadvantage—and what leaders can do to interrupt the cycle.

Systems Dynamics: The Importance of Avoiding Gender Bias in Performance Reviews

In today's turbulent and uncertain global business environment, traditional organizational planning and strategy methods are insufficient, as they often assume stability that is no longer present (Chermack, 2011). A systems approach to strategy helps leaders navigate this complexity and achieve optimal outcomes. This article introduces organizational leaders to the basics of Systems Dynamics and Systems Thinking, focusing on how to use these concepts to improve decision-making in performance reviews. Causal loop diagrams are presented as a useful tool to guide organizations in transforming their Performance Review Processes, moving from gender-biased feedback to a more equitable future state.

Systems Dynamics Overview

Systems Dynamics involves creating simulation models that help us better understand social and corporate systems. Everything exists as systems or parts of systems (known as subsystems), ranging from the micro to the macro level (Anderson & Johnson, 1997). Systems consist of a complex web of interrelated and interconnected causes and effects.

This means that one component within a system inevitably impacts one or more other areas within the same system, and often affects systems outside of it as well. These concepts describe the phenomenon at the heart of Systems Dynamics. Let’s explore systems further, the idea of systems thinking, and how leaders can formulate and implement effective strategies by being purposefully aware of and consistently considering the principles of Systems Dynamics.

What Is a System?

Everything from an atom, the fundamental building block of matter, to the entirety of the cosmos can be classified as a system. A system is a complex whole made up of interrelated, interdependent, and interactive components, which can be either physical or intangible. These components work together continuously to achieve a specific purpose within a larger system (Anderson & Johnson, 1997). For example, the components of physical systems include tangible objects, while the components of intangible systems include processes, policies, interpersonal relationships, information flows, feelings, values, and beliefs (Anderson & Johnson, 1997). In essence, systems are vast networks of interconnected nodes (Anderson & Johnson, 1997).

In other words, a system can be defined as any interconnected group of elements that operate together as a unit (Cornish, 2004). We exist within systems and are continuously influenced by them in every aspect of our lives, such as the natural environment, family, education, healthcare, organizational structure, and government (Anderson & Johnson, 1997). For a system to function optimally within a larger system, all of its parts must be present and arranged in a way that allows for interactions, fluctuations, feedback, and adjustments to flow continuously. This circulation is essential for maintaining the system's stability (Anderson & Johnson, 1997).

By exploring systems and understanding their behavior, we empower ourselves to function more proactively and effectively within them. We can shape our quality of life and desired future by anticipating unpredictable behaviors (Anderson & Johnson, 1997). Within and between systems, constant reciprocal changes (causes) occur, leading to various consequences (effects). This dynamic interplay is the essence of Systems Dynamics, which can be best understood, effectively communicated about, and appropriately acted upon through the practice of Systems Thinking.

Systems Thinking

Systems Thinking is a learned skill that provides a framework and set of tools for understanding issues as parts of a larger system (Anderson & Johnson, 1997). Unlike many Western languages that tend to emphasize linear cause-and-effect relationships (for example, "x causes y"), Systems Thinking adopts a nonlinear perspective. It allows us to discuss a web of dynamic, complex, interconnected, interdependent, and circular relationships that make up the most challenging problems (Anderson & Johnson, 1997).

There are five key principles that support Systems Thinking: (1) "big picture" thinking, (2) balancing long- and short-term perspectives, (3) awareness of the complex, dynamic interdependent nature of systems, (4) consideration of both measurable and immeasurable factors, and (5) recognition that we all belong to and function within systems and that we constantly influence these systems while being influenced by them (Anderson & Johnson, 1997).

Systems Thinking emphasizes closed interdependencies, focuses on understanding wholes instead of just parts, and highlights the importance of interconnections (Anderson & Johnson, 1997). In discussions about complex issues, Systems Thinking provides clear guidelines and visual tools that help reduce ambiguities and miscommunications while revealing insights and implications through easily memorable models (Anderson & Johnson, 1997). For instance, causal loop diagrams, which will be introduced later in this article, enhance the Systems Thinking process by emphasizing the dynamics of a problem and uncovering subtle yet significant differences in perspectives (Anderson & Johnson, 1997).

Ultimately, Systems Thinking offers innovative approaches to: (a) communicate how we perceive the world, (b) collaborate more effectively to understand and address complex issues, and (c) engage in adaptive thinking that continuously responds to changing environments (i.e., dynamic systems) (Anderson & Johnson, 1997).

Systems Dynamics

Systems Dynamics combines insights from organizational studies, behavioral decision theory, and engineering to provide a theoretical and empirical foundation for understanding relationships in complex systems (Anderson & Johnson, 1997). To effectively grasp and assess Systems Dynamics, we must appreciate the interconnections between different components of a system and integrate these connections into a comprehensive view of the entire system (Anderson & Johnson, 1997). Understanding and responding appropriately to Systems Dynamics requires active awareness—observing, sensing, intuiting, measuring, and adapting—of the environment. This awareness allows us to develop accurate dynamic strategies and action plans based on current needs as well as anticipated future needs (Canton, 2015).

We exist as systems composed of subsystems; we are part of larger systems and constantly influence and are influenced by them. These systems are continually in flux, ranging from larger entities like galaxies to smaller ones like atoms (Cornish, 2004). Everything exists in a state of constant change, where connections are continuously formed and broken within and among systems (Cornish, 2004).

In the context of business, a systems approach emphasizes the relationships among elements rather than the elements themselves. This is because the relationships (and interactions) among components shape events (Cornish, 2004). By adopting a systems approach, we broaden our understanding of how events occur, allowing us to suggest probable outcomes (Cornish, 2004) and providing a framework for effective preparation, proactive strategies, and appropriate responses to change.

However, the interrelationships, interdependencies, and interactions among a system's components can be challenging to perceive without clear and simple visual representations. Causal Loop Diagrams (CLDs) serve this purpose by facilitating the visualization of the reinforcing and balancing loops present in systems dynamics.

Causal Loop Diagrams: An Overview

Causal loop diagrams (CLDs) serve as powerful graphical representations of the intricate systemic structures that underpin various processes, allowing leaders and strategists to delve into the dynamic interplay between different variables that may have previously gone unexamined (Anderson & Johnson, 1997). These diagrams function as straightforward yet insightful maps, illustrating the interconnectedness within a closed-loop system characterized by complex cause-and-effect relationships. By employing CLDs, individuals can create an environment conducive to hypothesizing and testing potential solutions to problems, all without the risk of real-world repercussions (Anderson & Johnson, 1997).

Typically, a well-constructed CLD features several key components: (a) one or multiple feedback loops that reflect the cyclical nature of interactions, (b) clearly defined variable relationships depicting how one element can influence another, and (c) inherent delays that highlight the time lag between cause and effect (Anderson & Johnson, 1997). In the realm of organizational systems dynamics, such diagrams are especially relevant as they often operate within closed-loop systems. These systems may exhibit a range of characteristics, such as reinforcing loops that amplify change, balancing loops that strive for equilibrium, and various combinations of these elements, all of which depend on the unique nature of the interconnections present within the system (Gordon, 2009). By visualizing these relationships, stakeholders can better navigate and influence complex organizational challenges.

The Value of CLD’s Resolving Complex Issues

Causal loop diagrams (CLDs) serve as powerful tools for illuminating the intricate structures of complex systems, effectively shedding light on their inherent complexities. By maximizing simplicity, CLDs assist leaders in grasping the nuances of nonlinear systems (Boeing, 2016), enabling them to identify and understand the interplay among various subsystems, as well as the potential complications arising from these interactions (Anderson & Johnson, 1997).

These diagrams elegantly illustrate the cause-and-effect relationships that define a system, striving to encompass all elements that drive change. However, it is vital to acknowledge their limitations: (a) they do not account for the various forces or obstacles that can either facilitate or hinder change, both of which are essential for accurate predictions; (b) they cannot guarantee that every factor influencing the system is included; and (c) they may not reliably depict the current or future state of reality (Gordon, 2009).

While CLDs excel at generating clarity through simplification, they also reveal complex systemic structures and dynamic interrelationships that may have previously been overlooked (Anderson & Johnson, 1997). Therefore, it becomes crucial for strategists to remain cognizant of the fact that the underlying causal structures fundamentally shape ongoing events and give rise to systemic behaviors (Schaffernicht, 2010). In essence, the power of CLDs lies not just in their ability to simplify, but in their capacity to illuminate the profound connections within a system.

Women’s Careers Suffer from Biased Feedback

Organizations are increasingly aiming to create healthier and more effective feedback cultures. This transformation can enhance member satisfaction and improve both individual and organizational performance, as it ensures that people's voices are heard and their feelings are taken into account (Namazie, 2019). In feedback cultures, members develop growth mindsets, feel empowered to share ideas and concerns, and experience a general sense of recognition and appreciation. This environment encourages proactivity and creativity (Namazie, 2019). Furthermore, the positivity associated with feedback cultures leads to a reduction in wasted time and money for the organization (Namazie, 2019). However, it is important to note that performance review feedback can often be subject to significant gender bias, which can have disproportionately negative effects on women's careers.

In many feedback cultures, while organizational members are encouraged to give and receive feedback regularly, outgoing feedback often lacks effectiveness and may even be counterproductive. Research indicates that this is especially the case during performance reviews when the feedback recipients are women. Specifically, women often face the following challenges: (a) they are reviewed more harshly and subjectively; (b) they are held to higher standards of personality and behavior than men; (c) they frequently do not receive appropriate credit for their work; (d) they are often given vague and outcome-unrelated feedback; and (e) they are expected to be exceptional communicators, unlike their male counterparts, who are seen as "technical experts" (Cecchi-Dimeglio, 2017; Correll & Simard, 2016; Snyder, 2014).

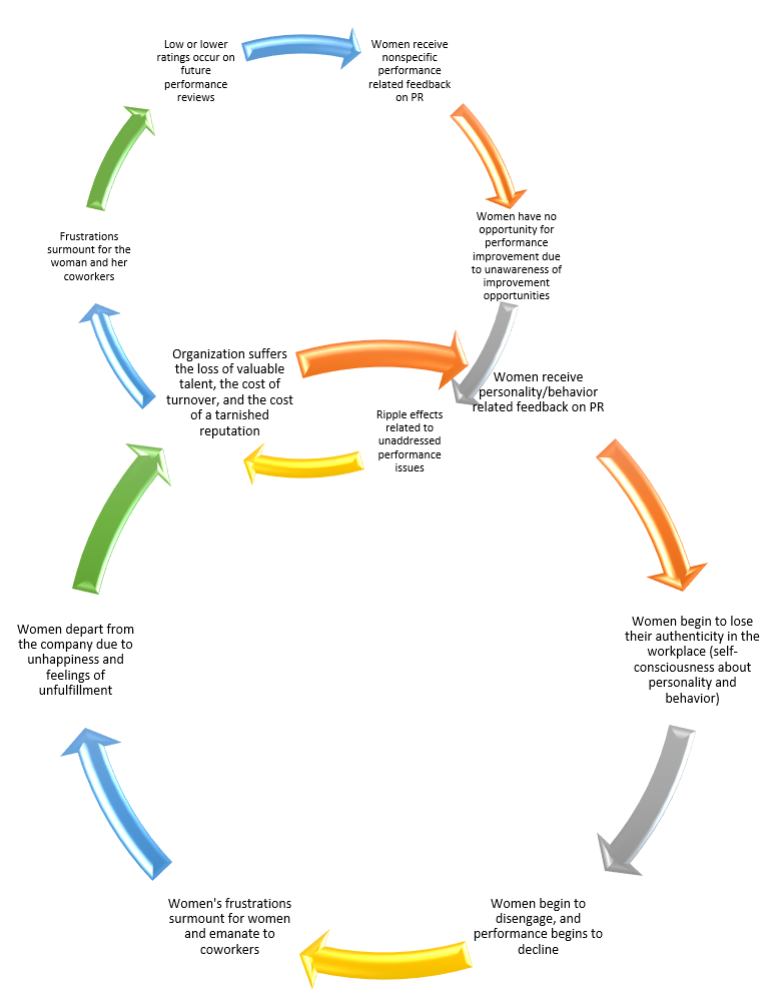

The following causal loop diagrams illustrate the current state of the performance review feedback process, which will later be compared to a desired state.

Current State CLD

In the diagram below, we can observe some of the immediate consequences of unstructured and unintentionally gender-biased performance review feedback given to women. When women receive vague, non-performance-related feedback, it can lead to negative effects.

For instance, women may begin to lose their sense of authenticity and feel less comfortable being their true selves at work. This situation can result in disengagement and a decline in performance, ultimately causing frustration and prompting many women to leave the organization. Such departures can have significant negative impacts on a company's bottom line. Furthermore, when women miss opportunities to enhance their performance due to this feedback, the organization also misses out on the benefits of their potential improvements.

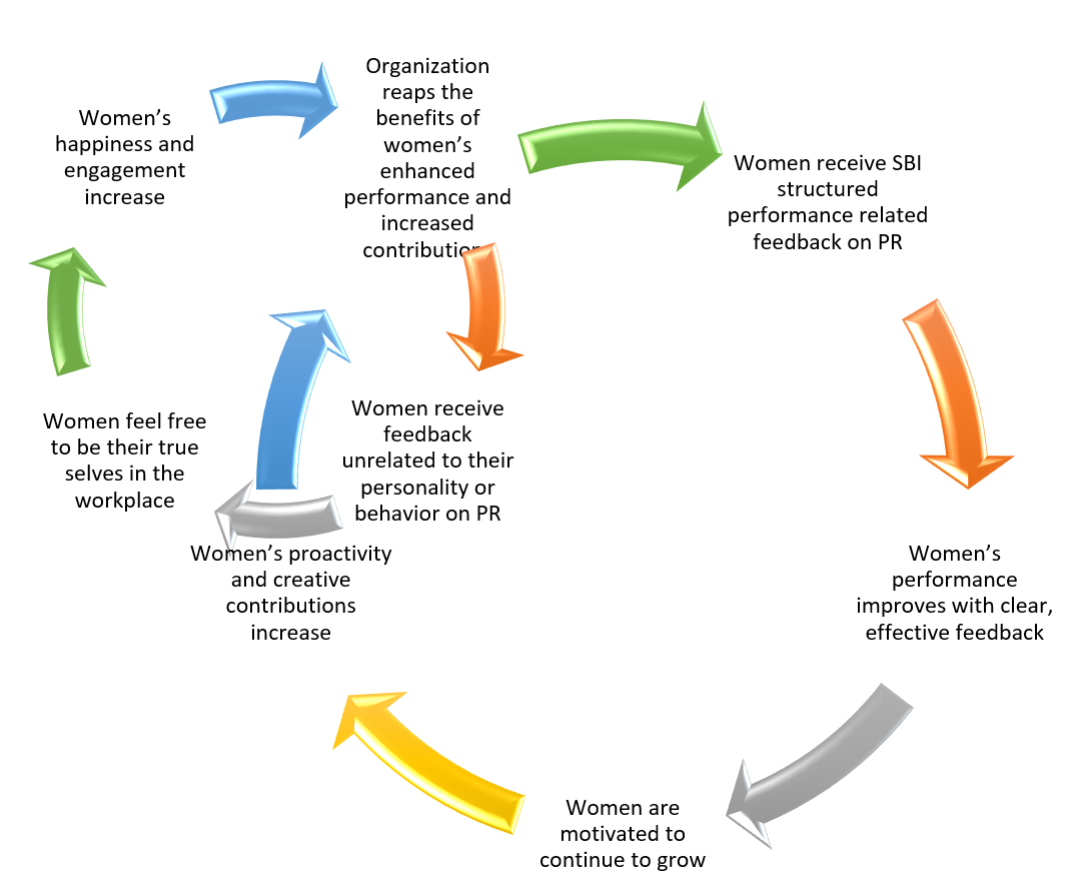

Future State CLD

To enhance performance, organization members can use structured feedback tools, such as the Situation-Behavior-Impact (SBI) model. This model emphasizes that effective feedback should include a clear description of the Situation, an account of the observed Behaviors, and an explanation of the Impact those behaviors have on the feedback giver (Center for Creative Leadership, 2020). Using this approach can significantly alleviate the anxiety of providing feedback and reduce the defensiveness that the recipient may otherwise feel (Center for Creative Leadership, 2020).

In this scenario, women in the workplace receive structured, objective, and unbiased feedback—not influenced by gender—which serves as a foundation for their improvement and growth plans. As a result, these women may feel more motivated, which can lead to an increase in their positive contributions. By focusing on their performance rather than their personalities or unrelated behaviors, women can express their true selves at work, leading to greater happiness and engagement. This situation appears to be beneficial for both the women and the organization, as the improved Performance Review process supports mutual growth and success.

Conclusion & Call to Action

In today’s VUCA environment, strategic leaders must employ a systems approach to effectively assess, respond to, and prepare for change in order to gain a competitive edge. It is essential for leaders and strategists to zoom out to the system level, assessing factors that might otherwise be overlooked. Implementing Causal Loop Diagrams (CLDs) is a straightforward and effective method to enhance problem-solving and decision-making processes, thereby increasing the likelihood of optimal preparedness for change and its impacts.

To eliminate unconscious gender bias in performance review feedback, organizational leaders must use structured feedback tools, such as the Situation-Behavior-Impact (SBI) method. This approach demands that feedback clearly defines the Situation, describes observable Behaviors, and explains the Impact of those behaviors on the feedback provider. Adopting this structured feedback method delivers substantial benefits to both the individual receiving feedback and the organization as a whole.

Sources

Anderson, V. & Johnson, L. (1997). Systems thinking basics. From concepts to causal Loops. Waltham: Pegasus Comm., Inc.

Boeing, G. (2016). Visual Analysis of Nonlinear Dynamical Systems: Chaos, Fractals, Self-Similarity and the Limits of Prediction. Systems; Basel, 4(4), 37. http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.regent.edu/10.3390/systems4040037

Canton, J. (2015). Future smart: Managing the game-changing trends that will transform your world. Da Capo Press.

Cecchi-Dimeglio, P. (2017). How gender bias corrupts performance reviews and what to do about it. Retrieved from:https://hbr.org/2017/04/how-gender-bias-corrupts-performance-reviews-and-what-to-do-about-it

Center for Creative Leadership. (2020). Use Situation-Behavior-Impact (SBI) to Understand Intent. Retrieved from https://www.ccl.org/articles/leading-effectively-articles/closing-the-gap-between-intent-and-impact/

Chermack, T. J. (2011). Scenario planning in organizations: How to create, use, and assess scenarios (1st ed.). San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc.

Correll, S. & Simard, C. (2016). Research: Vague feedback is holding women back. Retrieved from: https://hbr.org/2016/04/research-vague-feedback-is-holding-women-back

Cornish, E. (2004). Futuring: The exploration of the future. World Future Society.

Gordon, A. (2009). Future savvy: Identifying trends to make better decisions, manage uncertainty, and profit from change. New York: AMACOM.

Namazie, P. (2019). Why a feedback culture matters – and how to establish it. Eurasian Nexus Partners. Retrieved from https://eunepa.com/why-a-feedback-culture-matters-and-how-to-establish-it/

Schaffernicht, M. (2010). Causal loop diagrams between structure and behavior: A critical analysis of the relationship between polarity, behavior and events. Systems Research and Behavior Science, 27(6), 653-666. https://doi.org/10.1002/sres.1018

Senge, P. (2014, December 15). Systems thinking for a better world. Alto Systems Forum 2014 [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0QtQqZ6Q5-o&feature=youtu.be

Snyder, K. (2014). The abrasiveness trap: High-achieving men and women are described differently in reviews. Retrieved from:https://fortune.com/2014/08/26/performance-review-gender-bias/